Bamboo in Sogetsu

The techniques used when handling bamboo in Sogetsu works, have been passed down to the present day, with the Sogetsu history related to this material.

Bamboo for Hiroshi Teshigahara

It was Hiroshi Teshigahara, the third Iemoto, who began to concentrate on bamboo and make it a particular material as his speciality in ikebana.

Along with Hiroshi’s original words, let’s look back at his bamboo works that fascinated the world.

I was amazed at the resilience of the bamboo in forming 180-degree arches in heavy snowfall and still being able to withstand the weight of the snow, which was what made me turn to bamboo as a material.

I had hoped to use it someday, but it turned out to be a spur of the moment decision to use it in ikebana.

Hiroshi’s first encounter with bamboo came from his days living in a pottery studio in Fukui. Entranced by the abundant nature around him, Hiroshi was deeply moved with the resilience of bamboo, as it bowed under the heavy snowfall. He also saw bamboo waving in the strong winds from the sea as if they were giant creatures.

For some time now, I have been experimenting with various spatial expressions using bamboo materials. As I mentioned earlier, in Fukui, I was amazed at the resilience of the bamboo in forming 180-degree arches in heavy snowfall and still being able to withstand the weight of the snow, which was what made me turn to bamboo as a material. I had hoped to use it someday, but it turned out to be a spur of the moment decision to use it in ikebana.

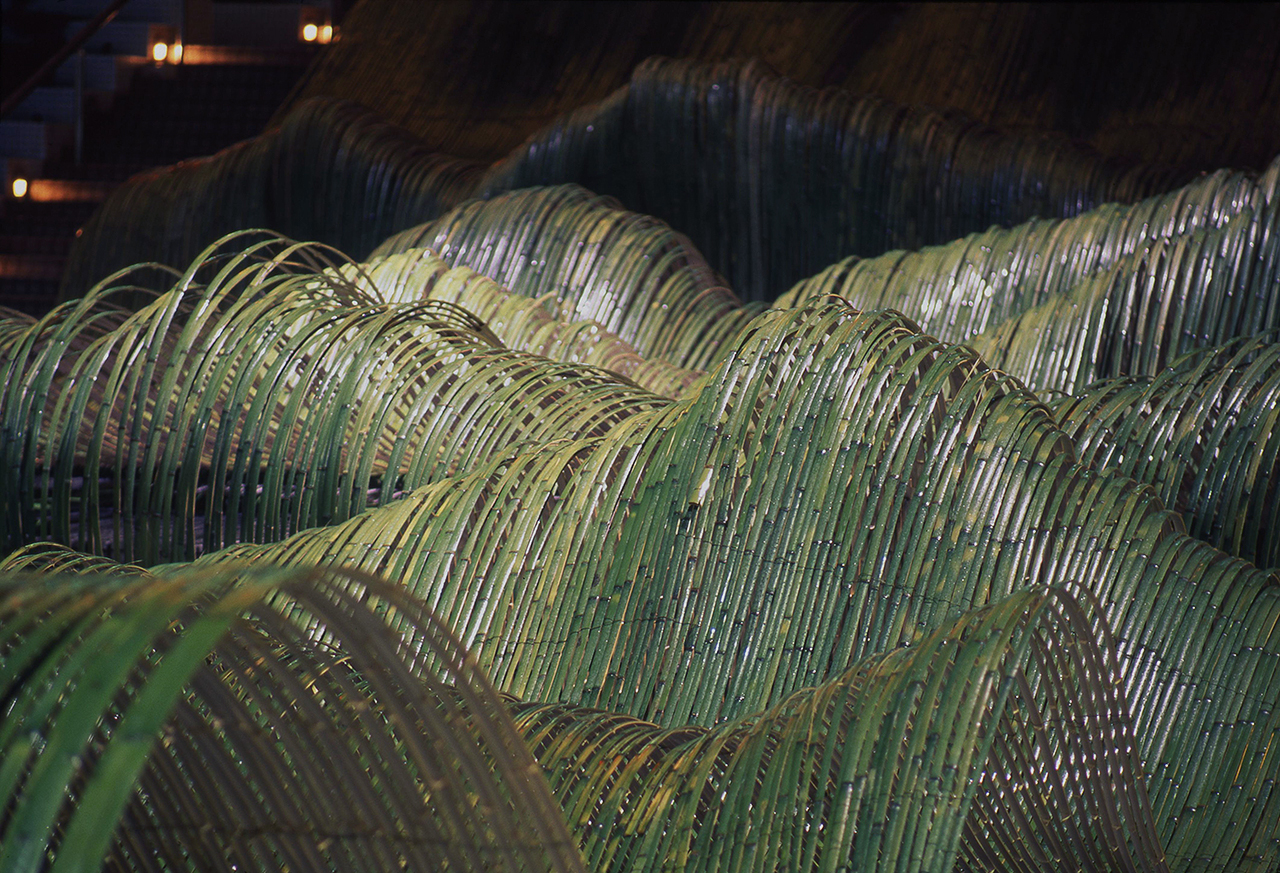

This material, bamboo, can be formed into straight or curved lines, allowing for the expression of a variety of forms. My first work with bamboo was “Takejin” (bamboo man) created in 1982 at the Shiseido Art House Museum in Kakegawa City, Shizuoka Prefecture. When I split pieces of bamboo down the middle and put them on the lawn with the split side down, a humorous image emerged of a large gathering of people standing up on the lawn. Then doing the same thing, but this time in a different place, where the work is standing up in the water. This outdoor production was not only an experiment in bamboo, but also a new experience for me where I could see how plant materials can be used against the backdrop of Mother Nature.

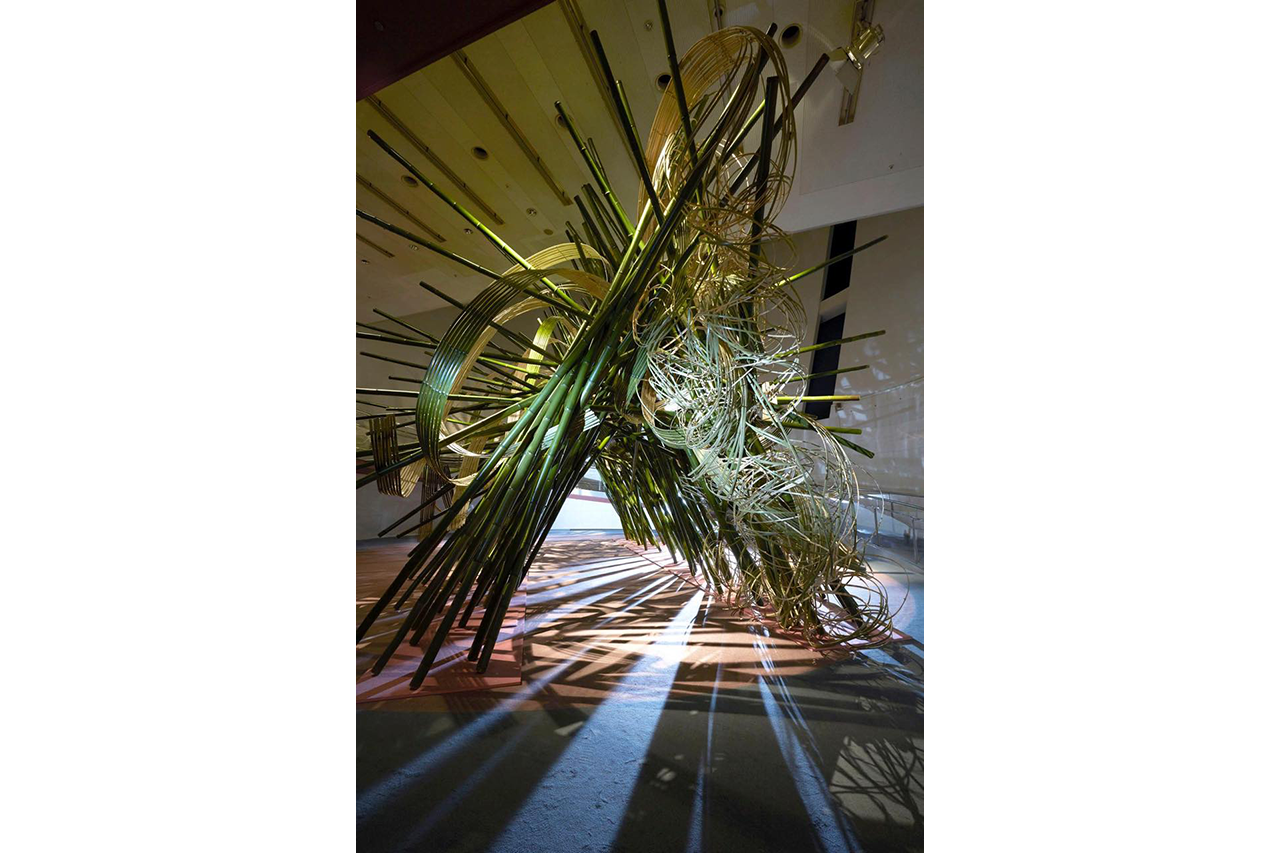

Since then, I have created numerous large-scale bamboo installations, including at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul. Bamboo especially has the beauty of curves. I am interested in using these organic curves of bamboo to create a completely different and unexpected space out of the box of modern architecture and to wrap people within it. My ikebana, which began with spatial composition, appears to be aimed at enveloping people in such plants. It could be called a space to be experienced.

Hiroshi Teshigahara,

“Furuta Oribe: The Avant-Garde in Momoyama Tea Bowls” (in Japanese)

I am now fascinated by the wonder of bamboo as a material.

The primary reason for this is that bamboo itself is pleasing to look at.

Beginning with “Space, Blue and White” at the Tama District Sogetsu Exhibition in February 1982, Hiroshi started presenting works made of bamboo. “Takejin” (1982), created at the Shiseido Art House Museum, was the first work to use the bamboo splitting technique and was a direct link to his later bamboo installations.

In 1987, the Teshigahara Hiroshi Exhibition: Bamboo – Kokyusuru Kukan (breathing space) was held at the Sogetsu Kaikan and the Nihombashi Takashimaya Department Store. There, he attempted to create a corridor-like space in a different dimension with bamboo and wrap it with plants.

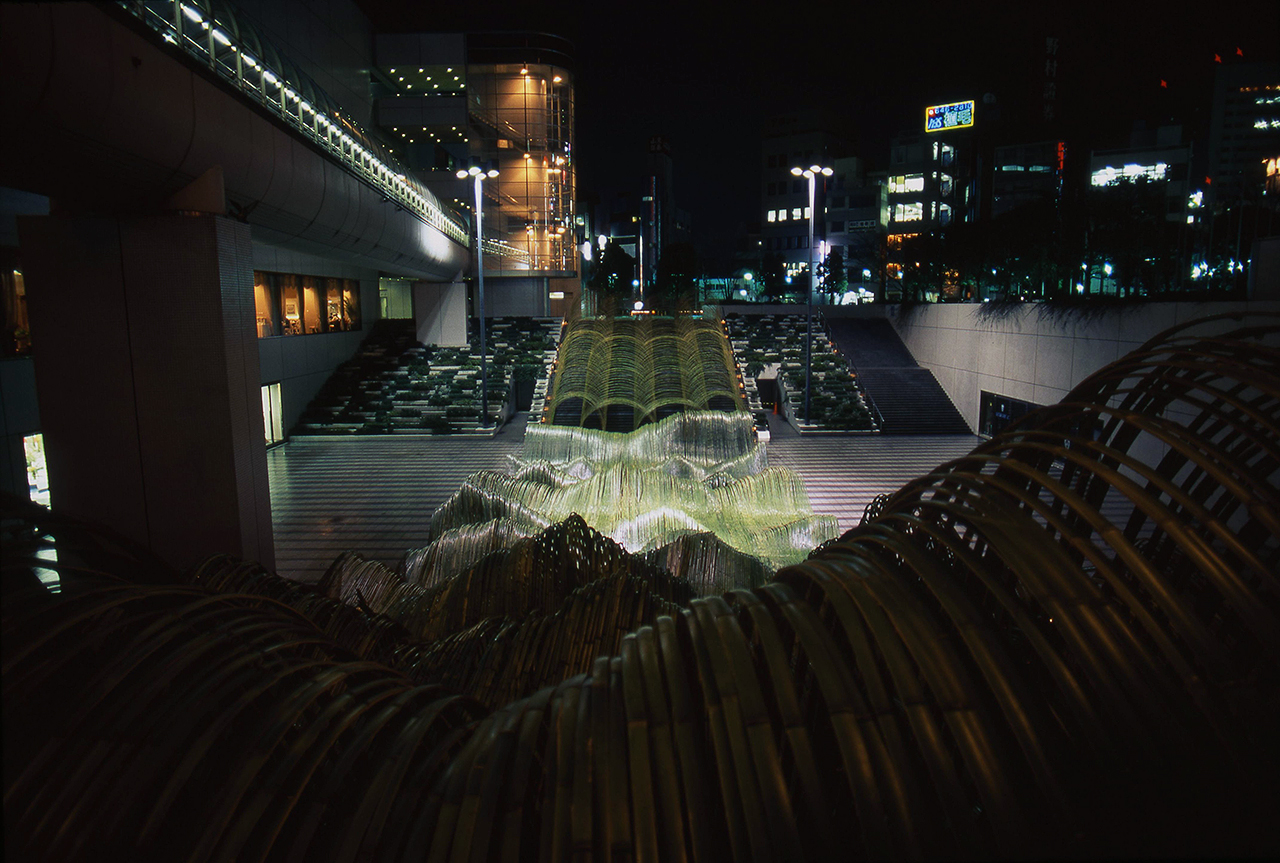

Hiroshi subsequently held large-scale solo exhibitions at the Marugame Genichiro Inokuma Museum of Contemporary Art (1994), the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art (1997), and overseas at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea in Seoul (1989), Palazzo Reale in Milan, Italy (1995), and the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington D.C. (1996), where he used bamboo freely according to his artistic sense. The spectacular installations of undulating and bending bamboo running through the space, transcending the framework of ikebana, were highly acclaimed globally as a work of art.

I am now fascinated by the wonder of bamboo as a material. The primary reason for this is that bamboo itself is very pleasant to look at. The shape itself is great. It is also resilient and flexible. For this reason, it is possible to create forms of straight and curved lines using only bamboo. This is very attractive to me. All shapes are either straight or curved, which build up to form various shapes. In other words, various molding methods are possible.

Furthermore, by using bamboo to create a huge space, people can walk through it. The people who pass along then also become an element of the work. People are also a part of that formative space, so to speak. In that space, the relationship between the object to be appreciated (the flower) and the person who appreciates it disappears, and the two coexist. It is the same as the “world where the tea master and guests become one” in Rikyu’s tea ceremony. I have long hoped to create such a world combining humans and plants.

It was my father, Sofu’s style to use driftwood often as a material because he liked the organic strength of wood. Using bamboo as a material is a divergence from his way.

Hiroshi Teshigahara,

“My Discovery of the Tea Ceremony: What is the Origin of Japanese Beauty?” (in Japanese)

I want to pursue whatever kind of mental exchange is possible there.

For this purpose, bamboo is desperately needed.

Hiroshi also used bamboo on the stage and for tea rooms.

The opera “Turandot” (1992) in Lyon, for which he designed and directed the staging, received high acclaim for its bamboo tunnel and Japanese papercraft, and his new Noh play “Susanoo” (1994) at the Festival d’Avignon surprised people by creating a bamboo Noh stage in a stone quarry.

His tea room construction using bamboo began as a simple setup in the Sogetsu Plaza at the Sogetsu Festival ’87, which later developed into the Shun-an. At the Numazu Grand Tea Ceremony’s “Daen” (1992) and the Paris Grand Tea Ceremony’s “Shun-an” (1993), he created a space resembling a tea whisk with bamboo pieces descending from a ceiling of split bamboo arranged in a circular pattern.

In 2000, Shun-an was set up in the Sogetsu Plaza, an innovative installation using bamboo panels made of round bamboo assembled in straight lines. At the Japan Art Festival in Numazu that same year, these bamboo panels were deployed on a large scale in the pine forests of Numazu Park, and that became the last tea house Hiroshi created.

Once I created a temporary enclosure made of bamboo, with a table and seating to enjoy tea in its center, people were lured by its casual atmosphere and enjoyed the moment of “chanoyu,” which some had never experienced before, without any awkwardness.

My goal of “playing with space” is moving away from the stand-alone ikebana that we only look at, and toward the creation of an environment that embraces people. I want to pursue whatever kind of mental exchange is possible there. For this purpose, bamboo is desperately needed. This affinity frees people’s minds. My installations may be a big leap from ikebana.

However, the time in which this composition can be maintained is the same as the length of a flower’s life, and when time passes, it disappears without a trace and remains only in people’s memories. In the pursuit of affluence, semi-permanent cold spaces made of steel, glass, and concrete were created all over Japan. And inside them, things are packed tightly, and people are stuck in a state of immobility. Isn’t now the time to question whether such a constricted state of immobility is genuinely affluent or not?

Monthly magazine Bungeishunju, May 1994 special issue

Bamboo for Akane Teshigahara

Sogetsu, now under the leadership of its fourth Iemoto, Akane Teshigahara, continues to present even more dynamic bamboo works in a variety of spaces based on her refined techniques.